Get Next Shodhyatra Update:

Phone:

079-27913293, 27912792

Email:

shodhyatra@sristi.org

GANGAGARH (BULANDSHAHAR) TO DAULA (BAGHPAT)

December 26, 2006 to January 3, 2007

The Eighteenth Shodhyatra drew explorers and innovators from across India to Western Uttar Pradesh, where traditional rural culture persists in an uneasy truce with sprawling urban expansion. This journey was unique in that our path skirted within 30 km of Delhi, starting from a village more than 120 km away. It allowed us to connect with the isolated rural villages and the bustling industrial areas in the same trip. Thus, we could observe many villages where people were able to retain their regional culture, traditional practices, and local biodiversity. But we also found serious sustainability issues that can be attributed in part to the encroaching city, and an influx of some times irresponsible industrialization, and unplanned urbanization.

But these could also be traced to lesser sensitivity to the need for maintaining soil fertility, agro-biodiversity, and adopting sustainable pest management etc. If a river by the side of which we walked, looked more like a filthy drain than stream of fresh water, we could only blame ourselves for forgetting the history of this civilization, which had been spawned on the banks of great rivers.

CHRISTMAS IN GANGAGARH

Shodhyatris (fellow walkers and explorers) from across India converged in Gangagarh village on December 25, 2006, the Holy X-Mas day. The walk involved a path from Gangagarh to Daula, presenting us contrasting perspectives about need for preserving some of the healthy traditions and running in haste to catch up with metropolitan culture. A total of 80 Shodyatris participated in the journey. These explorers included students, professionals, farmers, and innovators from Bihar, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Karnataka, Uttranchal, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Chattisgarh, and Delhi. Distinguished yatris included Mr Rajendra Singh, a native of Daula who has revolutionized water conservation in Rajasthan. Several activists of Tarun Bharat Sangh joined us in the beginning and took care of the last leg of the yatra. A team from BBC London joined the walk. They have already produced a radio program and covered the news about the Shodhyatra after experiencing what Honey Bee network does to recognize, respect and reward grassroots knowledge holders.

A senior innovation officer from TATA Quality, also walked the Shodhyatra for a day to explore the possibility of using the experience of Honeybee Network, SRISTI and NIF in increasing the creative capacity of India for the TATAs, just as faculty from some of the leading educational institutions also participated. Likewise, several students joined us and some young children and youth also walked ahead of others inspiring every one with their energy.

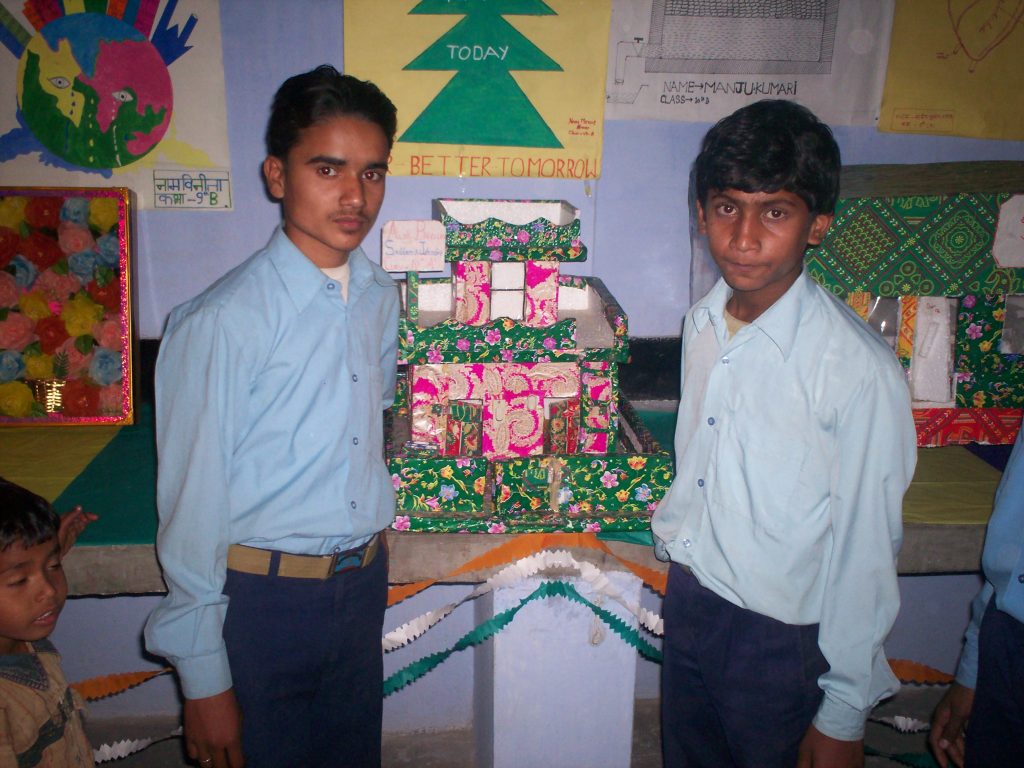

The Shodhyatra began on the morning of December 26th with a tribute to late Lt Alok Gupta, son of Dr G P Gupta and Ms Daya Gupta, and a celebration of grassroots creativity at SB Alok Memorial Higher Secondary School. Highlights of the opening meeting were the demonstration of innovations by the local children, felicitation of two women centenarians, and recipe and biodiversity contests. A cultural program was presented by the students on Christmas day including a very interesting debate about the pros and cons of the scientific advances and their effect on everyday life.

A Shodhyatri commented during the ceremony that more knowledge was transferred from grandparents to grandchildren in that one day than over the course of last several years.

TWO-WAY KNOWLEDGE EXCHANGE

The Shodhyatris traversed 34 villages over the course of the eight-day journey, stopping to hold meetings and share success stories of the villagers who used traditional knowledge and contemporary creativity to solve their local problems. In Agora village, where the yatris took their first nights rest, the presentation on the innovations from the Honey Bee database stimulated a wonderful discussion on the relevance of grassroots innovations in solving local problems. On being told about the importance of water and resource conservation, the villagers underlined the irony and demanded that we discuss these issues with the wasteful urbanites as well.

In order to maintain the creative momentum generated by the Shodhyatra, every village was encouraged to establish Shodh Panchayats (experimenters councils), like those being initiated in Gujarat, and make Village Knowledge Registers (VKRs) that could be linked with the National Register of Grassroots Innovations and Traditional Knowledge maintained at NIF.

However, not all meetings were formally planned. Most of them were spontaneous dialogues with inquisitive people we met on the road, and others were impromptu responses to interesting and/or curious people we met during the walk.

In one particularly interesting incident in Chipiyana village, Mr Avdhesh Kumar Chaudhary of the village approached the Shodhyatris to share his experience. He was working in a printing factory, and had just finished his night shift at the factory. Knowing that he would be unable to attend the morning meeting, he told us about a tree called Basendu (Diospyros montana Roxb.) growing near the dog temple and told us the story of how one of his relatives from Kanpur had noticed a peculiar property of the tree that when he had visited the village for a marriage. After a few days of returning to his home village, the relative, Mr Ram Chander Yadav asked Avdesh to send him two kilograms of this trees leaves. On inquiry, he informed him of its powerful medicinal properties. This story exemplifies the varied and winding paths that knowledge transfers can take! Mr Avdhesh was keen to tell us about it because he feared that if he had come after taking rest, we would have left the village for the next destination. How rare and reassuring is such impatience to share!

MECHANICAL INNOVATIONS

Shodhyatris came across numerous mechanical and energy related, general purpose as well as agricultural innovations that aimed at simplifying the day to day activities in a somewhat unconventional manner.

An innovation we recognized on the very first day of the yatra was a battery for charging mobile phones made using cow dung. Naruttam Kumar, a young student from Gangagarh had developed this charging unit using cow dung, old cells, six containers and some ordinary wires under the guidance of his school teacher. The assembly requires putting two used cells in each of the six containers having cow dung and a small quantity of urea. Cells are interconnected in series thus producing current, which is then used to charge mobile phones or play radios. While cell phones could reach millions of houses in rural India, lack of regular power supply had posed a problem. Narottam with the help of his teacher had found a cheap, cost effective and simple solution to this.

While walking towards Chipiyana village, we noticed a tempo parked on roadside. A breakdown had taken place. Seeing us walking by, a person got down from the tempo and asked us who we were, why were we walking, and where we would go? We paused to answer his questions, not knowing that an innovation was going to be discovered. The person, Dr Das had observed us walking even earlier. He was curious, but being in the tempo, he could not ask us about our purpose. When we told him about the motive behind the Shodhyatra, his face sparkled. He had also known about an innovator. Dr Das also had a printing shop. The innovator, Mr Kamruddin Saifi had come to him to get the stickers printed of his innovative pedal break based fodder-cutting machine. He promised to bring Mr Saifi to our next stop in Chipiyana village. We felt very lucky to have discovered an innovation incidentally on the road. But was it really an accident? Had it not happened in Kerala and many other Shodhyatras? Is that not why we walked? These questions animated the yatris on the way, waiting for the dawn, next day.

Dr Das and Mr Kamruddin Saifi reached next day morning on time! Commercially available motor or engine powered chaff cutters do not have any arrangement to stop the cutter immediately after discontinuing power. In the case of any accident or problem, even when the power is switched off, the cutter continues to rotate for a while due to momentum in fly wheel. Sometimes, when accidentally the feeders hand gets pulled inside the gears along with fodder, the hand gets amputated due to the inertia of the heavy flywheel to which the blade is attached.

Mr Saifi pondered over this and developed a mechanism, which if employed would ensure a safe chaff-cutting machine. The innovative mechanism consists of a combination of simple mechanical clutch and brake, which is actuated by a foot operated lever. When one presses the lever, the flywheel of the chaff cuter instantaneously gets locked, and disengages the power source from the chaff cutter. One needs to re-open the lock to operate the chaff cutter again. Several research institutes and central agricultural research council had worked for years to develop a similar machine, but in vain. In almost every village we had noticed people with amputations due to this very lacuna in chaff cutter machines. We asked as to how much should be considered the value of a hand, a question, which baffled many people in the villages. When asked whether they would not like to know about a machine costing say 4-5000 rupees, which would save their hand, they all showed interest.

But the fact was that either the information about this brake pedal chaff cutter had not reached their villages, or they had not found it out. Why did not information about such an innovation reach villages few kilometers away from the place of innovation? Why did government research agencies not bother to diffuse this innovation when Kamruddin offered to provide the design and details of his innovation free of cost to them for the well-being of other farmers? They did not bother to visit him even once. Shodhyatris kept on discussing these questions wondering why did such innovations not have legs.

Another fortuitously discovered invention was Mr Prithvi Singhs extremely efficient washing machine, which can clean up to 100 clothes in 15 minutes and can be operated manually or electrically.

The Shodhyatris also came across Mr Foto Singh of Chamraval village, who had designed a manually operated paddy seedling planter. With the back and forth movement of the machine, mechanical fingers are actuated, which pick seedlings from the tray and transplant it into puddled soil bed. The machine currently enables farmers to plant three rows of paddy at once, but design improvements could eventually increase this figure to five, nine, or even eleven rows at a time.

Other new agricultural tools scouted during the Shodhyatra include Mr Fateh Singhs moped engine powered agricultural implement, Mr Ramesh Chandra Sharmas modified Enfield engine, Mr Shiv Kumar Singhs modified foot valve of pumping set, Mr M.D. Fazeels air compressor pump for tank filling, and Mr Chandra Pal Singhs sickle sharpening equipment.

AGRICULTURAL GENIUSES

Shodhyatris distributed samples of SRISTIs newly developed growth promoters and herbal pesticides in many agricultural areas, and honored villagers at the forefront of the organic movement. One such farmer was Mr Rajveer Singh of Bhoopkhedi village, who has been improving crop yields and quality in his guava orchard for the past five years by adopting organic practices.

Another farmer, Mr Ranveer Singh, of Kote Village, pointed out a new variety of mustard to the Shodhyatris. A few years ago, he had noticed a single plant with dark green leaves, high yield, thick seedpods, and synchronized fruiting in his mustard field. The pods of this plant mature at the same time, and their thick-skin resists shattering, minimizing the amount of grain lost in the field and during transport. The pods were set right throughout the branch beginning almost from the base. Mr Ranveer selected a few plants of this type and grew them separately in his fields. He hopes to commercialize it one day. The farmer breeder thus selected odd plants and a variety could emerge, as if that was the normal thing to do. Perhaps, innovation was actually a normal thing to do for many farmers like Ranveer.

Mr Veer Dutt Bhati during the meeting in Beel Akbarpur village told the Shodhyatris that he had found a way to induce lemon (Citrus limon (L.) Burm.f.) trees to fruit throughout the year.

He mentioned that he dug a small trench on the ground around the tree three to four times a year, and trimmed the fine roots around the main trunk. He observed that this practice resulted in a perennial lemon harvest, rather than just twice a year yield.

The overall yield of the tree reduces by a fraction,, but round the year, supply has its own advantage for the market as well as self-consumption. For those who have tried to store lemons would know that it is not easy to do so even if kept in a refrigerator. Veer Dutt had developed a technology for ensuring round the year supply of fresh lemons.

Conservationists like Ms Raj Sharma and her team members of the Ped Mitra (Friends of Trees) organization were honoured during the Shodhyatra. They had popularized the concept of growing trees among children so that on their birth days, each child would plant a tree. Thousands of trees had been planted in that manner.

The yatris also came across a stately very old fig tree outside Bamhetha that was being conserved by the villagers. The yatris together with the villagers took a vow to conserve the tree under all circumstances. It was an ironic sight. All around this tree, large fences and boards of new industrial township had come up. Shodhyatris prayed that this solitary remnant of a bygone era would some how be allowed to survive.

HERBAL HEALERS

The Shodhyatris felicitated a total of 53 healers for their contributions to veterinary and human medicine. Mr Rev Singh of Sarai Dulha was honoured for suggesting that eating 21 stone apple leaves (Aegle marmelos (L) Corr.) and 21 pepper seeds (Piper nigrum L.) Each day for 40 days could cure diabetes. Whether this is true or not can be said only after proper validation trials are undertaken, but the spirit of sharing such traditional knowledge had kept many rural societies healthy for so long.

A villager informed the yatris that one of his buffaloes was very sick and refused to eat. In response, Mr Rahmatkhan Solanki, a renowned veterinary healer, walking in the Yatra was called to diagnose and treat the animal. He instructed the host to keep the animal covered with a warm blanket and feed it kali jeeri (Nigella sativa L.). The buffalo slowly recovered and extra care is now being taken to keep others buffaloes warm during extreme winters in the village. Yatris who had slept overnight at that villagers house felt happy that some relief could be provided to an ailing buffalo.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS

Water conservation was another major theme of this Shodhyatra. Mr Rajendra Singh, a renowned leader of Tarun Bharat Sangh, Alwar described the traditional water conservation techniques to restore depleted ground water resources. He shared the story of reviving a dried river in Rajasthan. On reaching his home village Daula, he showed the yatris the two ponds where encroachments had been stopped as the collective need for groundwater recharge surmounted individual desires for utilizing the fertile land in the tank basin.

We crossed the visibly polluted Hindon River on the fourth day of our journey, and paused to discuss the causes of its decline.

Mr Rajendra Singh and Swami Yagyamuniji implored villagers to join hands and fight for their right to clean water. Swamiji also announced his plan to lead a yatra to Delhi along the banks of the Hindon River in order to build awareness for its clean-up movement. It was a very distressing sight to see a river, once known for its clean quality, almost black in colour. The state did not bother, and the industries all along the river violated pollution control laws with impunity. The social apathy made many Yatris reflect on the state of rivers back home in their own neighbourhood.

INSPIRING CHILDREN

Bio-diversity competitions were organized during the Shodhyatra to generate interest about biodiversity, conservation and traditional knowledge among children. Six such competitions were held in different villages throughout the Shodhyatra, witnessing participation of many children from different schools and villages on the way.

At Navodaya Vidyalaya, Baghpat, many students came up with interesting ideas. Sonali Tomar, a class VIII student, emphasized the need for revival of traditional healing practices, explaining how her grandfather got rid of his common cold when she served him an extract of Guava (Psidium guajava L.), Jamun (Syzygium cumini L.), Adu (Prunus persica (L.) Batsch.), and Lisode (Cordia myxa L. ). Savita Arya wanted to develop some mechanism through which the polluting gases emitted through chimneys could be used to run motor to generate power.

Nipin Kumar suggested that the pressure created while walking could be used to run a small turbine that has the potential to generate enough electricity to charge a mobile phone. Prashant was given a prize in the Idea Competition for suggesting that energy might be generated from noise in our surroundings through a sensitive membrane based trigger. Students at SB Alok Memorial Higher Secondary School also impressed the Shodhyatris with the models they presented at their science fair. Use of old batteries for heating water, a working model of metro rail, and a door which when opened, rang the alarm in the house, were some of the innovative models that caught the interest of Shodhyatris.

UNSEEN CREATIVITY OF WOMEN

Villagers working towards womens rights and education were felicitated during the Yatra. These honourees included Mr Mahipal Singh, for his education initiative at Pahasu girls Degree College, and a social worker Ms Maya Sharma for her work in the realm of womens rights advocacy and social reforms in Beel Akbapur. Ms Ruby Choudhary, a young woman from Sikroad who will be competing in the upcoming National High jump and Discus throw competition to be held in Bangalore was also honored.

In Laliyana village, the Shodhyatris committed to the cause of Equal Opportunities for acquiring Knowledge postponed an evening meeting because no woman came to participate in the discussion. There was a lot of discussion in the village. A lot of young people gave excuses as to why women could not be expected to come to the meeting place, a church compound, in the night. Some talked about people who were drunk, and thus might cause trouble. But Shodhyatris remained unconvinced. They did not want to compromise. There was a depressing feeling among the yatris and a slight gloom pervaded in the air. But it got converted into glee next day morning when women turned up in large number for the meeting at the same place. As a result, women not only attended the subsequent meetings, but also participated in the cultural events that followed.

It would have been so easy to adjust with the traditions of exclusion of women from such social opportunities of lateral learning but Yatris were happy that they could fight such a perverse tradition successfully.

Village women celebrated their cultural heritage, demonstrated their innovative capacity, and generated interest in the preservation of agricultural biodiversity in the three recipe contests held at Gangagarh, Chipiyana, and Laliyana.

The submitted recipes included minor millets, lesser known crops, or plants with medicinal value. More than 20 girls and women participated in the recipe contest, with interesting and innovative dishes with high nutritional value.

Particularly intriguing among the entries was a sweet made of spinach (Palak ki Barfi). Poonam and Sarita, two young girls who prepared the dish, were awarded first prize for their creativity. This burfi of spinach almost became a metaphor all through the Yatra then for creativity of women. In subsequent villages, a question would be asked as to whether anyone had eaten such a sweet and thus curiosity of men and women would be kindled about what the Yatra was all about.

Women were also found acting as guardians of traditional art in the villages we passed by. In Chipiyana a womens group, led by a very spirited elderly lady named Ms Murti Devi welcomed Shodhyatris with an impromptu performance of traditional song and dance. Notably, innumerable dung heaps were found along the roadside carved with beautiful and intricate patterns. Each dung heap had a unique design. This demonstrated that the rural women took any opportunity that they could to express their creativity. If only we would care to notice and appreciate and be inspired.

Veteran Shodhyatris were reminded of the courtyard they saw in Anand, Gujarat during a previous Shodhyatra where a young girl had spent countless hours scratching beautiful drawings, each different from the other, on the ground of her courtyard. Surely these creative outlets manifest that women are no less capable and innovative than men.

HUNDRED YEARS OF WISDOW : HONOURING THE CENTENARIANS

The Shodhyatris also sought to honour and document the lives and times of the centenarian men and women. The yatris felicitated a total of nine centenarians during the Shodhyatra, five of whom were women. Peeru Baba eloquently summed up the lesson of life, saying, “there is no way anyone can get happiness by hurting others.” Another centenarian, Mr Bodu Singh, told villagers and Shodhyatris that his secret to longevity is a diet rich in pure milk, butter, and curd. He also warned listeners about the health risks associated with addiction to alcohol, appealing to the younger generation to ‘please quit liquor.

Many villagers in Sikroad and Garhi Kalanjari took a pledge to give up their drinking upon the suggestion of Swamiji and centenarian Mr Bodu Singh. One man ceremoniously smashed his bottle of homemade liquor declaring that he would never have another drink! The villagers had witnessed the backlash of vices like alcohol abuse in the past, and were willing to pick up their traditional practices once again and reform their bad habits.

CULTURE AND VALUES

The Shodhyatris shared many beautiful Hindi and Gujarati folksongs accompanied by the harmonium on the New Year eve. Mr Richard Berenger of the BBC team delighted the yatris with his rendition of On Ilkley Moor Baht, a hilarious Yorkshire folk tune, which incidentally revolves around the theme of recycling. An amazing confluence of cultures, traditions of very different societies could be witnessed that evening. Mr Peter Day and his wife Romee Day also sang a song.

Ms Margaret performed a character from a Hindi film and many other Shodhyatris shared their musical skills.

While leaving Kote, the villagers told the yatris about the ancient ruins lying nearby. Though these ruins had been ignored for decades, a new movement was emerging to restore and preserve them. We also came across a very unique cultural heritage in Chipiyana; a dog temple, popularly known as the “Bhairav Mandir”.

FROM KNOWLEDGE TO WISDOW

Closing ceremony was officiated by two dynamic, respected scholars, Prof Yashpal and Dr Y P Singh. Dr Y P Singh is a remarkable teacher who has had an open school at his home in Hisar where MSc and PhD students would brainstorm on various scientific issues till late night. There are very few teachers who provide their students the freedom to learn and explore in this manner. He was always interested in getting together the farmers, scientific knowledge, and society. He appreciated SRISTI work, and said this Shodhyatra is the first attempt of its kind, focusing on seeking knowledge from people and linking it with science. He also talked about how such walks in quest of knowledge can lead to discovering some wonderful innovations on the way. “The amphibious cycle designed by Mr Dwarka Prasad Chaurasiya of Mirzapur, Uttar Pradesh, for example, did not come out of the laboratory, but by an unknown innovator staying in a remote area”, he added.

Prof Yashpal is the founder of the Space Application Center and former chief of the University Grants Committee. He has long been a champion of education in rural India (he called it Real India). He would often ask as in which schools had jewellers and watch repair mechanics ever studied. He advocated the establishment of vocational schools to train young people in skills used in everyday life. He asked the audience “Why do Indian classical singers cover one ear with their hand and raise the other hand in the air?, “How can a person hear his voice even with both his ears closed?”, and “Why does clapping ones palms together make a loud noise while clapping the back of one hands makes only a muffled sound?”. He revealed that he had once asked a friends daughter the reason why she closed her ears while singing? The girl replied saying that when she practiced singing, her music teacher would ask her to plug her ears with cotton. She had not been told the science of it.

Prof Yashpal explained that “When we talk, two kinds of vibrations are generated, one that reaches the microphone and is reflected to the ears, and the other that is generated from within and reaches a point in the brain where it is interpreted. When we close our ear, we are avoiding the disturbance caused by the reflection of sound from the nearby objects, and concentrate on the sounds generated from within. Similarly, the knowledge we receive is in pieces, and can be imparted to anyone through any medium. The people around us, the problems and joys we experience, all contribute to our knowledge. Everyone has a different way of thinking and doing things, which is captured beautifully by the Shodhyatra. It is the responsibility of every human being to innovate, while sitting passively as a consumer is disrespect to humanity”.

Prof Yashpal added that that he had recently visited a Childrens Science Congress in Sikkim attended by selected students out of 10 Lakh students who had participated, countrywide. About 500 students among them had researched on problems related to ecological balance. A book was created specially for the purpose, and a report was prepared, with the help of teachers. He stressed on the need to connect such movements with the broader goals of Shodhyatra, since children are important in moulding the face of the future India.

The purpose of this discussion was to encourage the inquisitive nature and stimulate people to learn from the things we see around us every day. Indeed, isnt that the purpose of the Shodhyatra? It is aimed to recognize that there exists a whole world of learning beyond the laboratory and the classrooms! A world where the learning is not restricted by the uni-directional clause of Lab to Land but witnesses an exchange of knowledge between the Lab and the Land for a sustainable and an efficient future.

FLICKR GALLERY